1. Preamble

This post is a shallow investigation, as described here. As we noted in the civil conflict investigation and telecommunications in LMICs investigation we shared earlier this year, we have not shared many shallow investigations in the last few years but are moving towards sharing more of our early stage work.

This investigation was written by Helen Kissel, a PhD candidate in economics at Stanford who worked at Open Philanthropy for 10 weeks in summer 2022 as one of five interns on the Global Health and Wellbeing Cause Prioritization team. We’ve also included the peer foreword, written by Strategy Fellow Chris Smith. The peer foreword, which is a standard part of our research process, is an initial response to a piece of research work, written by a team member who is not the primary author or their manager.

A slightly earlier draft of this work has been read and discussed by the cause prioritization team. At this point, we plan to learn more about this topic by engaging with philanthropists who are already working on tobacco, extending the depth of this research (particularly on e-cigarettes), and digging deeper into countries which have seen big declines in their smoking burden (e.g. Brazil).

2. Peer foreword

Written by Chris Smith

It was in 1964 that the US Surgeon General published a report which linked smoking cigarettes with lung cancer, building on research going back more than a decade. The report told readers that smokers had a 9-10x relative risk of developing lung cancer; that smoking was the primary cause of chronic bronchitis; that pregnant people who smoked were more likely to have underweight newborns, and that smoking was also linked to emphysema and heart disease.

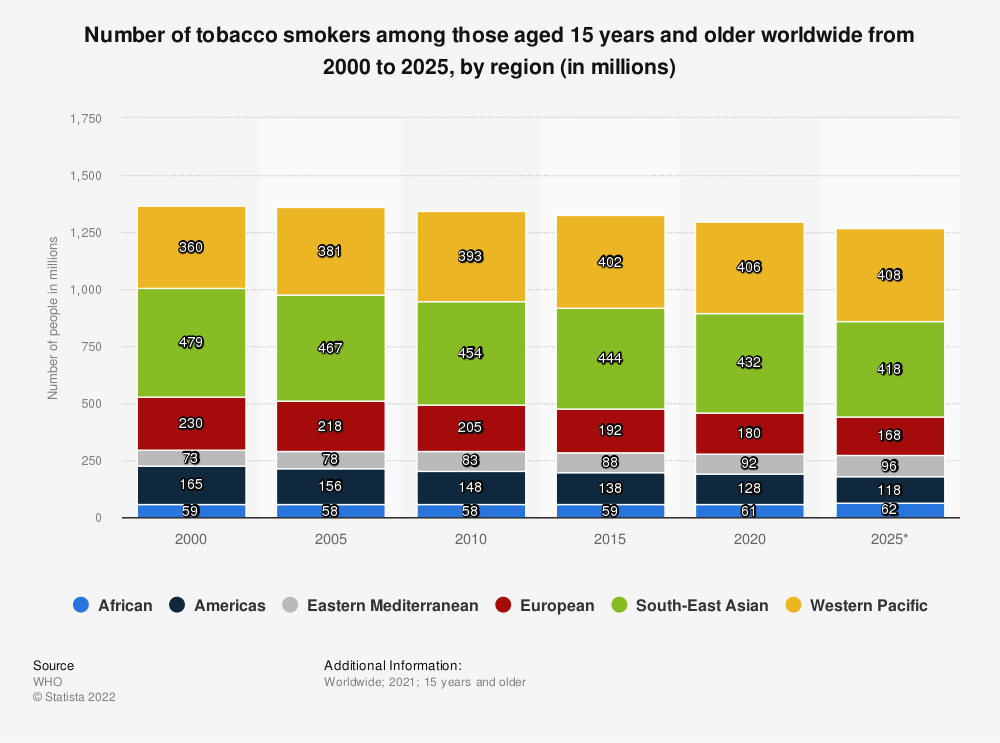

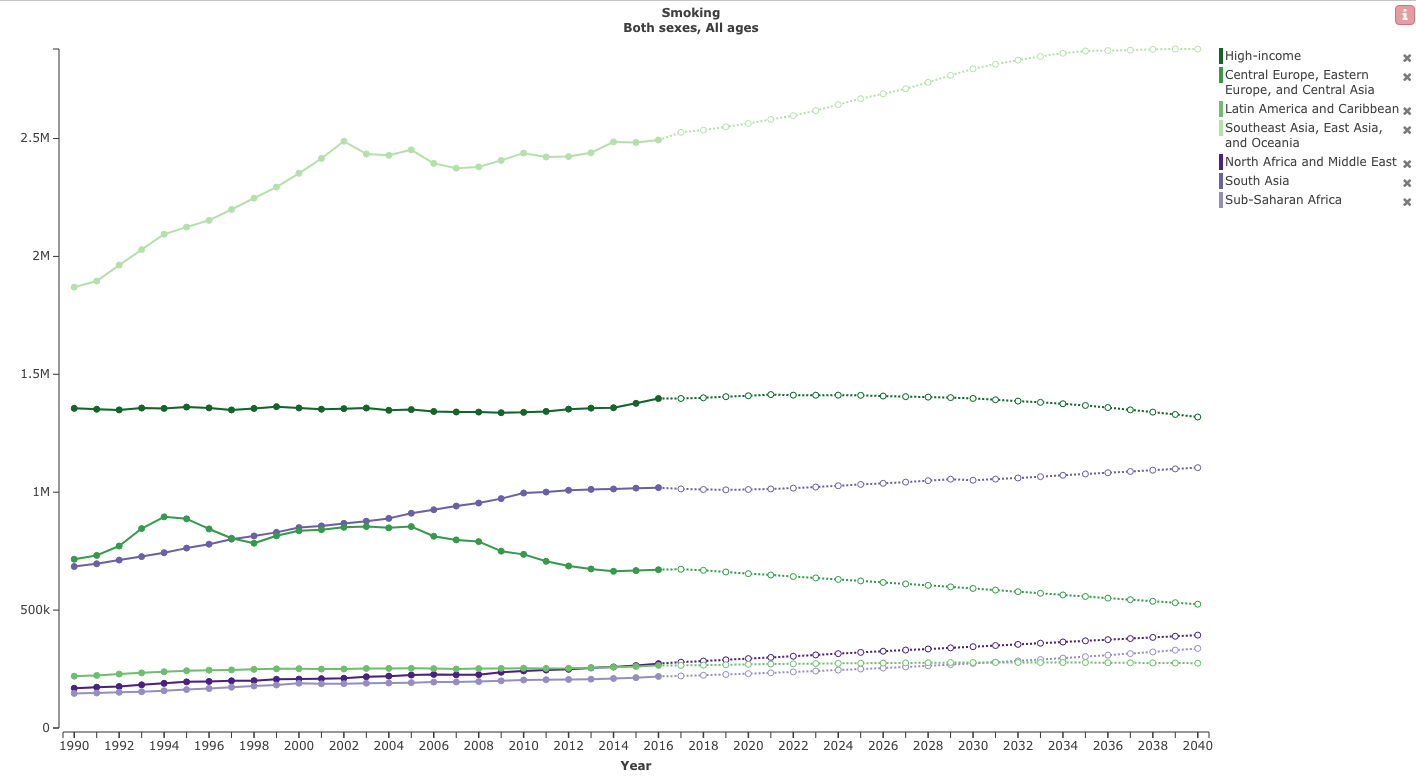

In this shallow, Helen reports that nearly sixty years later, there are ~1.3B tobacco users, and that smoking combustible tobacco remains an extraordinary contributor to the global burden of disease, responsible for some 8 million deaths (including secondhand smoke) and ~230M normative disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) (~173M OP descriptive DALYs)[1] making it a bigger contributor to health damages in our terms than HIV/AIDS plus tuberculosis plus malaria. Moreover, the forward-looking projections are for only modest declines in the total burden as population increases offset a decline in smoking rates. As our framework puts it, we’ve got an important problem.

Helen walks through the conventional orthodoxy on tobacco control at a population level (higher taxes, marketing restrictions, warning labels) and on smoking cessation support (nicotine replacement therapy, pharmaceutical support). She estimates that a campaign for a cigarette tax which increased the retail price of cigarettes in Indonesia by 10% (a large country with a high attributable disease burden) would reduce tobacco consumption (and attributable DALYs) by 5%, having an expected social return on investment (SROI)[2] of ~3,300x, assuming a 3-year speedup, 10% success rate, and $3M campaign cost. Taxes are considered the single most effective policy measure, but going down the ladder to a moderate advertising ban, the subsequent expected 1% reduction in tobacco consumption and associated DALYs would have an SROI of ~500x. As with any of our shallow back-of-the-envelope-calculations (BOTECs), there is room to debate both the structure and the parameter choices. But I think that this is — when combined with the other material — a strong indicator that there could be relatively mainstream tobacco advocacy work which is above our bar in expectation. This suggests a somewhat tractable problem.

Ok, but isn’t this addressed? Don’t people already know that cigarettes are bad for you? We’ve spent quite a lot of 2022 reviewing the Gates Foundation strategy for global health (more science → better tools → better outcomes), but tobacco control has traditionally been a more Bloomberg Foundation-shaped area (campaigns → better laws → better outcomes). I have less of a feel for what counts as neglected or crowded in advocacy work, but Helen’s estimate of ~$76M per year from official development assistance and philanthropy doesn’t strike me as excessively crowded for a problem of this scale. It’s a lower number than I expected, but I don’t think my conclusion would be different if the estimate was 3x higher.

But then the question becomes “what should we literally do?”

I think this is where the trickier questions come up. One option would be to simply put more fuel in the existing tobacco control engine:

- Support the MPOWER policy package

- Perhaps focus on the countries on the margin which aren’t a focus for Bloomberg or Gates because of their prioritization (these are likely countries with smaller populations / smaller smoking burdens)

- Perhaps have a laser focus on taxation (which often has different stakeholders, such as ministries of finance rather than ministries of health).

The bolder step would be to focus on policies somewhat outside the mainstream, like scaling up pharmacological approaches to support tobacco cessation for smokers who know they want to quit, or supporting more liberal approaches to e-cigarettes / vaping. I’ve been following this debate at a low level for several years, and I’m increasingly convinced that these products have huge public health potential. Helen’s discussion of the evidence is well worth reading. If you want to go deeper, my suggestion is this National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report from 2018 which includes some interesting modeling on the net effects of e-cigarettes. I think her BOTEC of the historic value of vaping in the UK is somewhat conservative — she estimates it at ~8% of the total current health harm of smoking, or $16.6 billion in social return (the UK was starting from a relatively low base of harm given historic leadership on tobacco control).

All this said, if we consider going down an e-cigarette route, it’s worth engaging with the arguments against their liberalization: they’re not the most effective way to quit and could plausibly cannibalize from other quit attempts; almost everyone’s heard of e-cigarettes but almost nobody’s heard of varenicline; there are market incentives to sell addictive harm reduction products anyway, so it’s unclear what the role of a philanthropist should be, even before considering the fact that we’d be somewhat pushing against other parts of the public health community; technically, the biggest tobacco control foundation (the Philip Morris International-funded Foundation for a Smoke-Free World) already promote them, so it’s not clear that it is truly neglected.

3. Executive summary

Smoking is responsible for over eight million deaths every year. An estimated 173 million disability-adjusted life years (OP DALYs)[3] are lost to smoking annually, which is roughly equivalent to the health damages caused by HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria combined. Most of this burden (~75%) is in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), and while smoking rates are declining in most countries, the overall burden is expected to remain constant or increase as populations grow.

There are many existing nonprofit organizations working on tobacco control. In total, IHME reports that about $75 million in developmental assistance and philanthropic funding is spent each year on tobacco control in LMICs. The Gates Foundation and Bloomberg Philanthropies are two of the largest funders in this space. Gates mainly funds tobacco control in Africa, while Bloomberg focuses on large, mainly Asian countries. This means that there may be some relatively neglected small countries that could benefit from additional funding for tobacco control advocacy.

The World Health Organization (WHO)’s recommended framework to reduce demand for tobacco is known by the acronym MPOWER. The set of recommended policy areas are:

- Monitoring tobacco use prevention policies

- Protecting people from tobacco smoke

- Offering help to quit tobacco use

- Warning about the dangers of tobacco

- Enforcing bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship

- Raising taxes on tobacco.

Of these recommended measures, raising tobacco taxes seems like the most effective strategy. A preliminary BOTEC (back-of-the-envelope calculation) suggests that increasing the cigarette tax in Indonesia by 10% would reduce cigarette consumption by 5% and have an estimated SROI of ~3,300x, assuming a cost of $3m and a 10% chance of success. Smaller countries with a lower attributable burden would, all else being equal, have lower SROI.

A major challenge in tobacco control advocacy is pushback from the tobacco industry. In the US alone, the tobacco industry spent $28 million on lobbying against tobacco control policies last year at the federal level, with even more funding lobbying at the state level (ASH). In LMICs with relatively small public health departments, it can be difficult and expensive to get tobacco control policies passed. The cost and probability of success depend both on the amount of pushback from the tobacco industry and the complexity of the legislative system.

One alternative to traditional tobacco control policies is promoting the use of non-combustible tobacco products, such as e-cigarettes, for harm reduction. This strategy is very controversial, and thus essentially not funded by philanthropy.[4] The health risks of e-cigarettes seem to be at most 10% that of traditional cigarettes and, among smokers who want to quit, e-cigarettes increase cessation. However, I’m less certain about promoting e-cigarettes as a harm reduction strategy at the population level. My main uncertainty is in how much the availability of e-cigarettes actually affects population-level smoking rates — the evidence on this is very mixed. I have also found very little research on e-cigarettes for harm reduction in LMICs. Additionally, any policy that is likely to increase use of e-cigarettes should be accompanied by strong regulation of e-cigarettes to minimize their health risks and limit use by youth.

3.1 Case for / against

Why should we look more into this?

- Tobacco control has relatively little money spent on it, given the scale of the health burden

- Because cigarettes are so deadly (in the US, smokers have ~10 years lower life expectancy), even very small changes in smoking prevalence can have massive impacts.

- Unlike some public health problems we have looked into (e.g. water pollution, lead exposure), measuring progress in smoking consumption is relatively easy (there is global data on aggregate cigarette sales) and the mechanisms linking smoking to health impacts are relatively well understood and a matter of medical consensus.

- There could be huge health benefits from policies that incentivize consumers in LMICs to substitute combustible cigarettes for alternative forms of nicotine — and this is an area that (to the best of my knowledge) is completely un-funded by philanthropy.

Why should we not fund this?

- Global cigarette consumption is slowly declining, and tobacco companies claim they are moving towards a “smoke-free world” by promoting e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products. If smokers switch over to these products or other safer tobacco alternatives, the health risks will be significantly lower, and this could lower our projections of future DALYs lost to smoking.

- Due to tobacco industry pushback, it is relatively expensive to change policy in this area and there are already large philanthropic organizations (Bloomberg & Gates) involved in tobacco control. The “low-hanging fruit” of easy-to-change policies has probably already been picked, and the countries that still have bad tobacco policies are likely the most difficult countries to work with.

- Relatively neglected countries tend to have smaller populations. For this intervention to meet our bar, we’d probably have to think that policy intervention costs less in smaller countries (and it isn’t clear that this is the case).

3.2 Remaining uncertainties

These are some of the uncertainties that seem most important to address before we move forward in this area:

- Do e-cigarettes reduce smoking rates at a population level? I found many randomized controlled trials (RCTs) suggesting e-cigarettes help individuals quit smoking, but did not find any evidence on whether the availability of e-cigarettes lowered cigarette consumption at the country level.

- What are the health gains for dual-users of cigarettes and e-cigarettes who reduce daily cigarette consumption without fully quitting?

- What do we think the true probability of success is in passing tobacco taxation policy? As a next step, we should spend more time looking at past wins and failures of philanthropic spending in tobacco control.

- Do we think there are smaller countries where we could change tobacco tax policy at a relatively low cost?

- While drafting this shallow, I didn’t speak with any experts from the largest philanthropic organizations in this space (Bloomberg, Gates, Vital Strategies). We should prioritize getting better information on spending and how much additional money this cause area could absorb.

4. Importance

There are 1.3 billion tobacco users worldwide, and approximately half of all smokers will die from tobacco-related causes. Tobacco is responsible for over 8 million deaths annually (7 million from direct tobacco use, 1.2 million from secondhand smoke) (WHO, 2022). Approximately 75% of these tobacco-caused deaths are in LMICs, and 80% are in men. The most common causes of smoking-related deaths were ischaemic heart disease (21%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (20%), tracheal/bronchus/lung cancers (16%), and stroke (12%) (GBD, 2021). Jha et al., 2013 estimate, based on US survey data between 1997-2004, that smokers have a life expectancy 10 years lower than that of people who never smoked.[5]

The GBD estimates 229.7 million annual DALYs from tobacco (199.7m from smoking, 37m from secondhand smoke). Of these DALYs, 193.6M are from YLL and 36.1M from YLD. Most of those who die from smoking are adults — so if we adjust the GBD DALYs by .75 to be consistent with other Open Philanthropy DALY calculations, this gives ~172.5m DALYs. We value averting a DALY at $100,000 per DALY. This means the total health burden of tobacco is $17.3 trillion in OP terms.

4.1 Smoking rates over time

Tobacco control efforts began in the 1960s, and global progress began with the passing of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) in 2005, which includes a range of recommended strategies for reducing tobacco use.

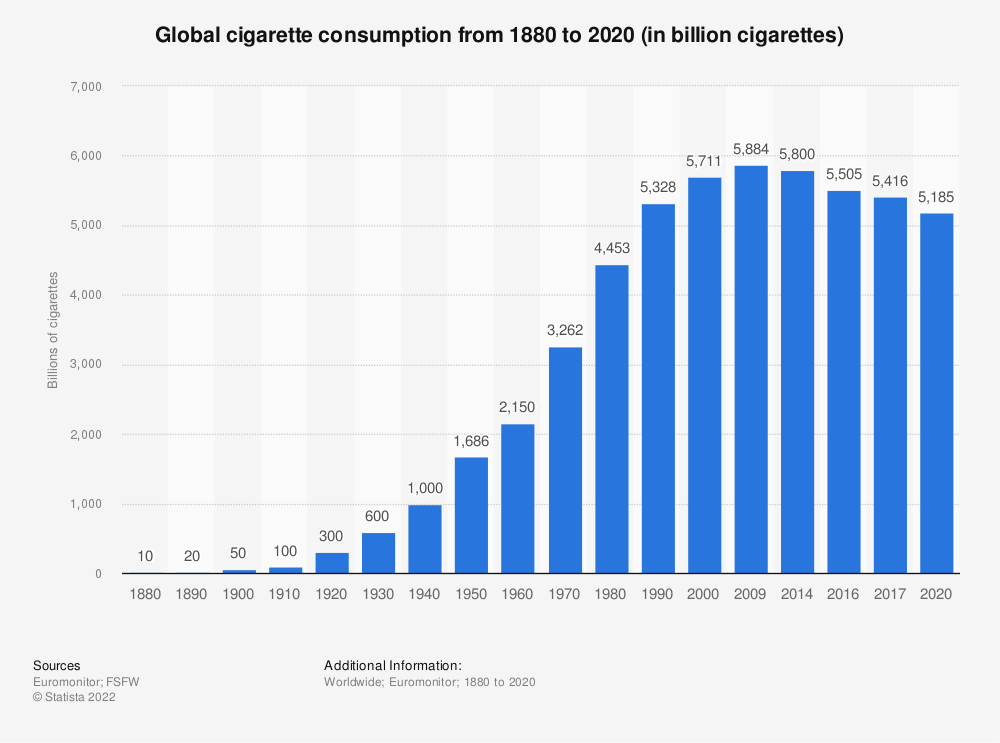

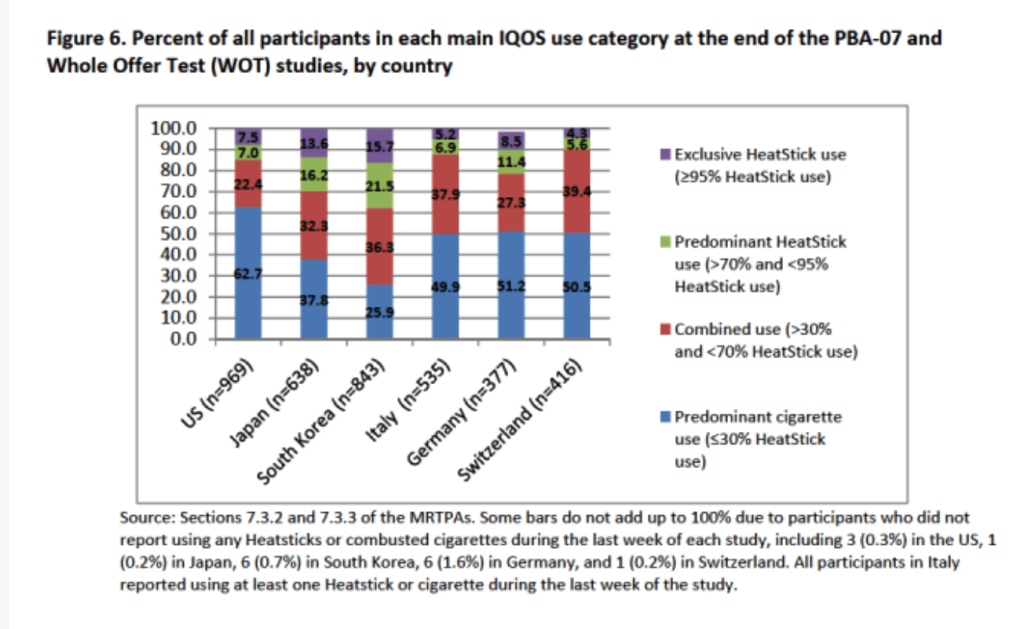

Since 1990, smoking rates have decreased in most countries, including LMICs. Between 1990 and 2019, global smoking prevalence decreased by 27.5% in males (37.7% in females) and global cigarette consumption has declined since 2009 (see figure below). There is substantial heterogeneity by country: smoking prevalence decreased by more than 45% in 10 countries,[6] and increased in others (20 countries for males, 12 for females).

However, in many LMICs, smoking rate declines have not been enough to offset population growth. 113 countries have seen an increase in the number of smokers since 1990 (GBD, 2021). This growth is concentrated in Africa, the Middle East, and the Western Pacific.

In terms of DALYs lost from smoking, GBD projections show a decline in rate (DALYs per 100,000 people) but projects that the aggregate number of DALYs will increase in some regions as their populations grow. China has been a main driver of the increase in Asia.

4.2 Assumptions

For all BOTECs, I only considered health effects. I also assumed that an x% decrease in cigarette consumption will reduce DALYs lost from smoking by x%. This is a huge simplification, and could be overestimating (or underestimating) the true benefits of lowering consumption for several reasons. A few factors I did not spend much time looking into:

- Cigarettes could have non-linear health effects. (For example, does smoking half the number of cigarettes per day reduce the health risks by half?) This applies to both cigarettes and e-cigarettes. It is also relevant for cigarette taxes, which lower both smoking prevalence and smoking intensity. In a quick search, I didn’t find a great answer for this beyond “smoking any number of cigarettes is still bad for you”.

- Smoking could matter more at different ages. Jha et al., 2013 found that adults who quit smoking at ages 25-34, 35-44, or 45-54 gained about 10, 9, and 6 years of life, respectively, compared to those who continued to smoke, and that smokers who quit before age 40 reduce risk of death from smoking by about 90%.

- Revenue from taxes. If tobacco tax revenue goes towards other public health measures, infrastructure, or lowering taxes, this could have large benefits. For now, I’ve assumed no benefit from additional tax revenue.

- Changes in disposable income. Tobacco taxes could either lower total spending on cigarettes (if smokers quit) or raise total spending (if continuing smokers don’t reduce consumption). In both cases, the income available for spending on other goods changes.

- Benefits of tobacco use. I have completely ignored any benefits smokers get from smoking. However, given that surveys suggest most smokers don’t want to quit, we may want to think more carefully about this assumption.

5. Neglectedness

IHME’s[7] spending data from 2021 shows $76 million in global health spending on tobacco control. Of this, $25 million comes from the Gates Foundation, $22 million from other private philanthropy (including Bloomberg Philanthropies), $22 million from the WHO (which includes $2.3m from private philanthropy and $1.9m from Gates), and the rest mainly from governments (US, UK, Germany, Japan largest contributors). IHME does not report recipient countries for recent years, but in 2018 all of the listed recipients were in LMICs. However, Bloomberg reports much more spending — $1b over the last 10 years. Some of the discrepancy could be explained by large one-time donations and spending on tobacco control in high income countries.

Analyzing this funding space was confusing because I couldn’t find exact numbers for how much money Bloomberg and Gates give to each of their many partners, and it was difficult to find information on how much money each of the Gates/Bloomberg partners spend on tobacco control each year. A surprising number had no spending data publicly available, and those who did report expenditures typically only had aggregate spending data that included many non-tobacco projects. If I had more time to work on this, I would prioritize trying to get better spending numbers and talking with other philanthropic organizations about where additional funds are most needed.

5.1 Neglected countries

From talking with experts in the area, the Gates Foundation’s tobacco control funding mainly focuses on Africa, while Bloomberg Philanthropies focuses on countries outside Africa, prioritizing the most populous countries. According to The Union (which co-manages the Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use Grants Program), Bloomberg has supported efforts in 50 countries but focuses mainly on the 10 countries with the highest prevalence of tobacco use: China, Brazil, Vietnam, Bangladesh, Philippines, Mexico, Pakistan, Indonesia, India, and Ukraine. Based on this, there may be some smaller countries that are relatively neglected by major donors. Below are maps of tobacco control policies from Our World in Data:

From these maps, it seems like Africa and parts of Southeast Asia have the weakest tobacco control policies.

5.2 Neglected strategies

The most neglected strategies are those outside the WHO’s recommended MPOWER framework.

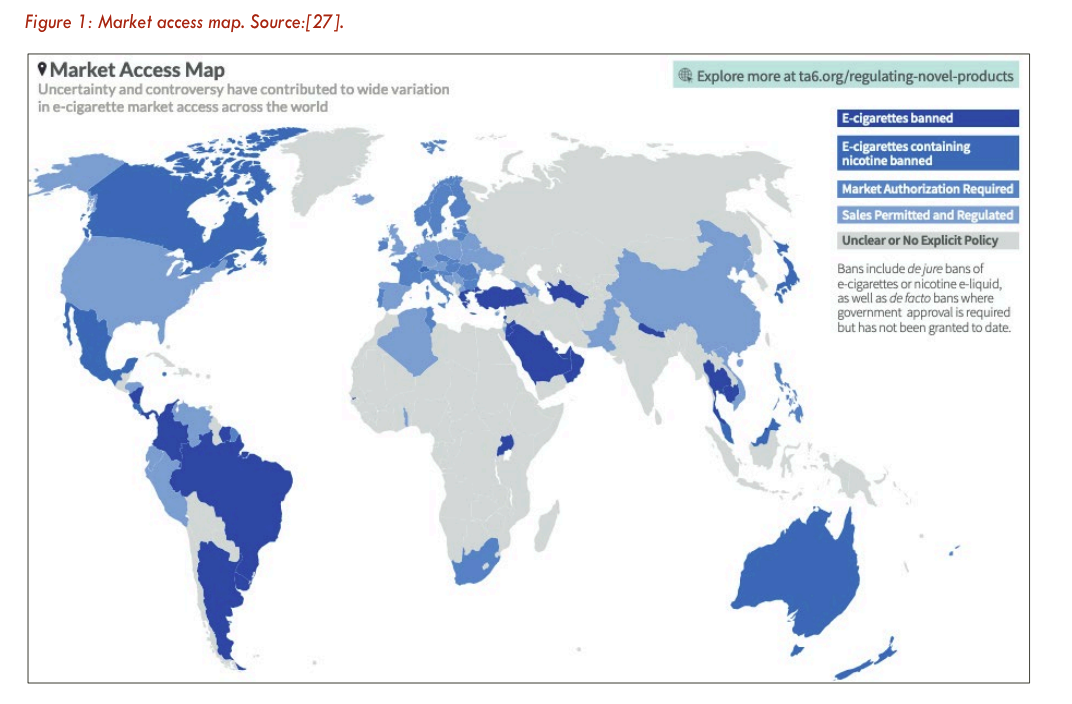

E-cigarettes for harm reduction. This intervention appears to be completely neglected by philanthropy. The idea is that e-cigarettes are much less dangerous for smokers than traditional cigarettes and may also help with cessation. In the e-cigarettes/harm reduction section, I discuss the nuances of why this may or may not be an effective strategy.

I have not come across any NGOs advocating for promoting e-cigarettes in LMICs. There are some organizations in favor of e-cigarettes for harm reduction in the US (e.g. CASAA), but it can be difficult to tell who is funded by tobacco companies in this area, and what research can be trusted (e.g. Foundation for a Smoke-Free World funds grants in LMICs on cessation and harm reduction — but is funded by Philip Morris International). Most philanthropists seem to be very opposed to funding e-cigarette promotion. For instance, Bloomberg Philanthropies funds campaigns to ban flavored e-cigarette products through the Protect Kids: Fight Flavored E-Cigarettes program and has committed $160 million to ban flavored e-cigarettes (NYTimes). Gates seems somewhat more open to harm reduction. From the Gates website: “Alternative tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, aren’t harmless, but they may be less harmful. We need to understand whether they could change the course of the smoking epidemic without addicting youth.”

Legal aid. One strategy outside the MPOWER framework is training legal experts to write better policies and fight against the tobacco industry lobby. There are some organizations working on this. The Anti-Tobacco Trade Litigation Fund, which is funded by both Bloomberg and Gates, provides resources to LMICs to pass tobacco control laws. The McCabe Centre in Australia trains government lawyers and policymakers to advance tobacco control laws. I did not find any estimates of how much funding is spent on legal aid, so I am unsure how much this space would benefit from additional funding.

Increased cooperation. Because there are so many organizations working on tobacco control, there could be gains from increased cooperation between organizations working in different regions or advocating for different policies. There could also be efficiency gains from combining work on alcohol and tobacco, since governments often think about these policies together. However, I am not sure how we could influence this.

6. Tractability

Because smoking is so deadly and the number of people who smoke is so large, even very small changes in smoking rates would result in large aggregate health benefits in DALY terms.

Bloomberg Philanthropies claims that it has saved nearly 35 million lives with ~$1 billion in spending (source). Even if we assume that only 1 year of life was saved for each of the 35 million people, this puts their claimed SROI at 3,500x (in terms of how OP values DALYs). However, I did not spend much time trying to find or validate the data behind this claim.

6.1 “Big Tobacco”

The top tobacco companies by share of the cigarette market by volume are China National Tobacco Corporation (CNTC) with 44%[8], Philip Morris International (PMI) with 14%[9], British American Tobacco (BAT) with 12%, Japan Tobacco International (JTI) with 8.5%, and Imperial Brands with 3.5% (Statista). The tobacco industry has huge profit margins (roughly 30% return on sales), and so has a tremendous amount of money to spend on advertising and lobbying. In 2020, four major US cigarette companies spent $7.8 billion on cigarette advertising and promotion in the US alone, mostly consisting of discounts to cigarette retailers (FTC, 2021). In 2020, the tobacco industry had 236 registered lobbyists in the US (~75% of whom were former government employees) and spent $28 million on lobbying against US tobacco control policies at the federal level. At the state level, the tobacco industry had 1001 lobbying registrations (ASH). This makes the area of tobacco control more challenging than other areas in public health, as you can expect large and well-funded pushback against any form of tobacco control policy.

6.2 MPOWER

The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) is a treaty that sets universal standards for tobacco control, such as banning sales to minors, offering help to end addiction, regulating contents of tobacco packaging, and banning tobacco advertising. As of 2017, 181 countries were parties to the FCTC and seven more (including the US) had signed but not ratified the treaty (FCTC). Many websites (e.g. ash.org) state that parties to this treaty are legally bound to implement evidence-based measures to reduce tobacco use. However, in practice I am not sure how much (if any) enforcement there is of this treaty.

In 2008 the WHO introduced the MPOWER measures, which are meant to serve as a framework for how countries should reduce demand for tobacco. The measures, with specific recommendations, are below (from Tobacco Free Kids)

Monitoring tobacco use prevention policies: Monitoring systems to track tobacco use, existing interventions, tobacco marketing, etc.

Protecting people from tobacco smoke: Smoke-free laws.

Offering help to quit tobacco use: Cessation services integrated into primary health care, quitlines, nicotine replacement therapy.

Warning about the dangers of tobacco: Health warnings or graphic images on cigarette packages, media campaigns using graphic images.

Enforcing bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship: Comprehensive advertising bans.

Raising taxes on tobacco: Taxing all tobacco products.

Most NGOs I have come across in the tobacco control space seem to agree that these are the best strategies to reduce tobacco use. In this investigation, I looked into raising tobacco taxes, graphic warning labels, advertising bans, and nicotine replacement therapy. Of these strategies, cigarette taxes have the strongest evidence behind them. The evidence is mixed that advertising bans, graphic package warnings and cessation services work alone, though they would likely decrease smoking rates in combination with other policies.

6.3 How many people want to quit?

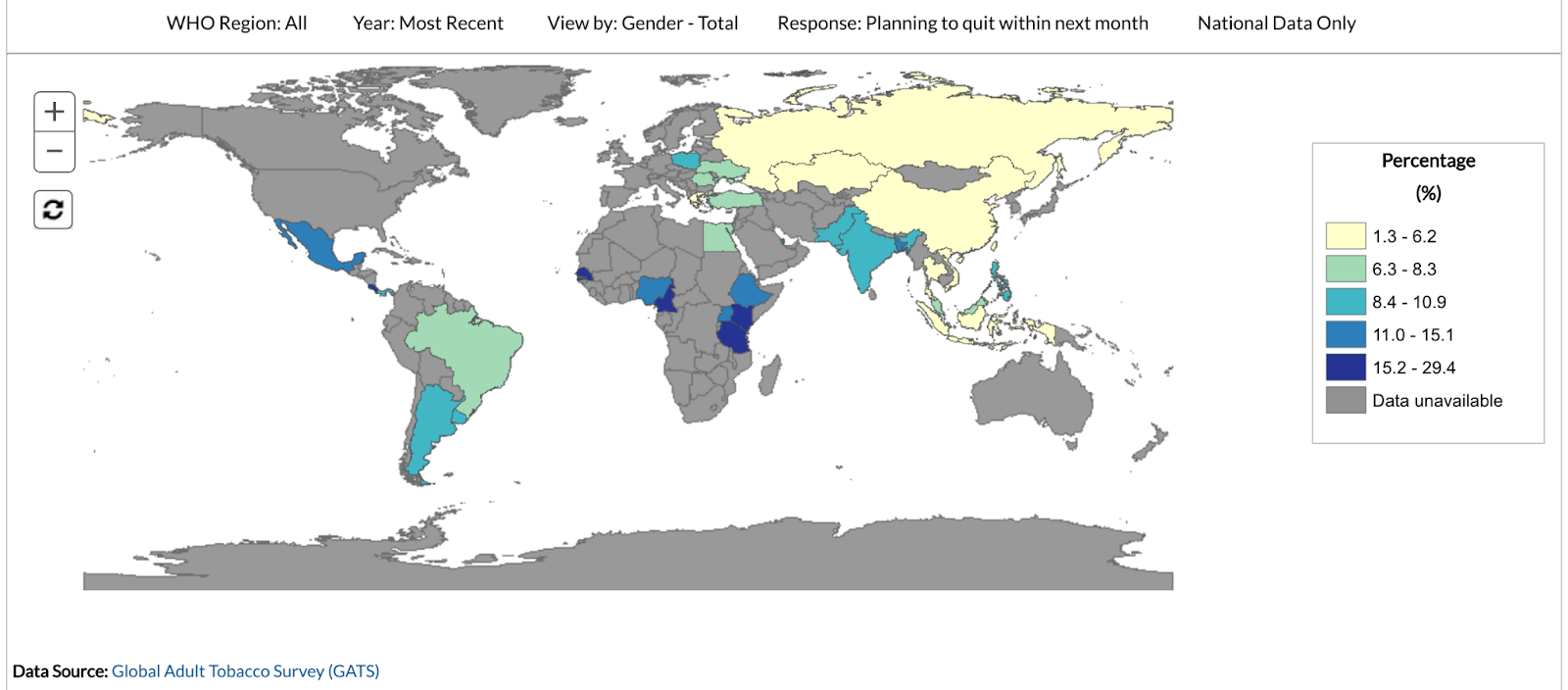

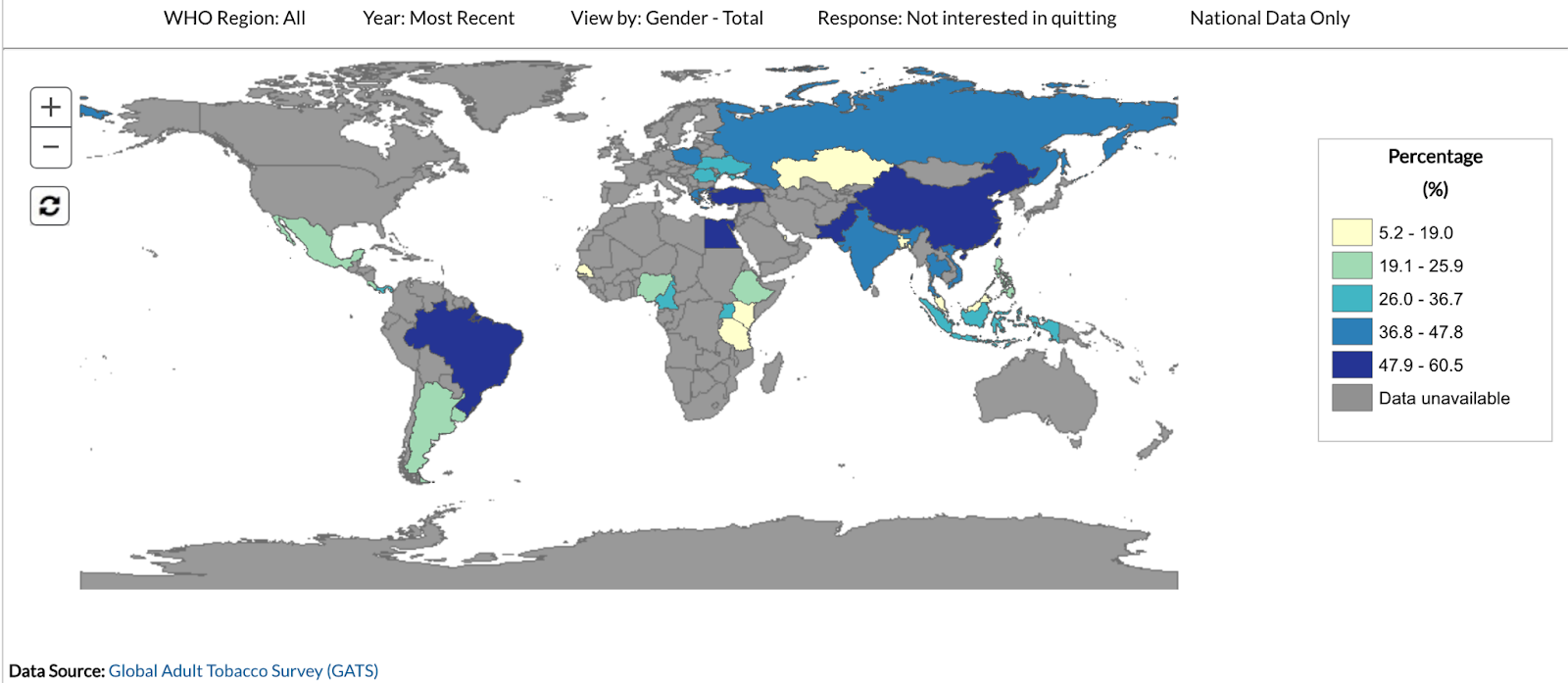

All forms of nicotine replacement therapy, and to some extent harm reduction methods, will only work if smokers want to quit smoking. In surveys, 50-60% of smokers in the US report wanting to quit; however, one expert I talked with guessed the true number was at most 40%. While I didn’t find great data for LMICs, the Global Tobacco Surveillance System (GTSS) has limited data from some countries on self-reported plans to quit (maps below, sourced from here). The percent of current smokers planning to quit within the next month seems like a reasonable proxy for how many are actively trying to quit, and this number seems to be <10% for most countries with data.

Quitting smoking is very difficult. In the US, only about 8% of smokers who attempted to quit in 2018 were successful (FDA, 2022). Because of this, lowering smoking initiation rates is much more effective in the long run than increasing cessation.

6.4 Nicotine replacement therapy

Traditional nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) options include nicotine patches, gum, pouches, inhalers, nasal sprays, and lozenges. These forms of NRT have very high safety ratings, do not cause cancer, and are much less addictive than cigarettes. There is some mixed evidence on cardiovascular disease, but the risk is certainly much lower than that of smoking. Using these forms of NRT for smoking cessation is well-accepted by public health officials (cdc.gov).

NRT is intended to be used only for short periods to help with quitting, and the addictive potential mainly depends on the speed of delivery.[10] Without NRT, 1-year quitting success rates are 3-5% (Hughes et al., 2003).[11]

- One overview of the literature (Wadgave & Negesh, 2015; Hartmann-Boyce et al., 2018) estimates that NRT increases the chance of successfully quitting by 50-70%.

- However, the British Smoking Toolkit Study found no increase in quit success when using over-the-counter NRT without professional support. They reconcile this with prior RCTs by suggesting that the professional instructions and follow-up are crucial to the success of NRT (Royal College of Physicians, 2016 pg. 100).

- Additionally, Amodei & Lamb, 2013 found that making NRT available over the counter in the US did not meaningfully change smoking rates in the US, and that the proportion of smokers attempting to quit who use NRT is fairly small (8-21%).

- The CDC reports that in 2015 around 30% of US smokers reported using medication when trying to quit (CDC). Amodei & Lamb attribute the low takeup rate to perceptions that NRT is ineffective or unhealthy, and association between withdrawal symptoms and NRT. It seems likely that another reason NRTs are less popular is because the slow nicotine delivery system means users don’t feel effects for approximately 30 minutes with patches and gum.

NRT access alone would probably not significantly affect smoking rates, but it might increase the effectiveness of other interventions. Effective strategies for enhancing the effects of NRT access might include:

- Offering free NRT in conjunction with higher tobacco taxes (including coupons for free NRT with tobacco purchases)

- Increasing awareness of programs that cover the cost of NRT (if any are available; in the US, most health insurance covers NRT)

6.5 Pharmaceuticals for cessation

Bupropion is an antidepressant that is also prescribed to help with symptoms of nicotine withdrawal. The FDA approved Bupropion for smoking cessation under the name Zyban in 1997.

Varenicline (brand name Chantix[12]) is a 2x daily pill that lowers the enjoyment of nicotine and can be prescribed to help quit smoking. It was first approved by the FDA in 2006 and appears to be more effective than Bupropion.[13] Many RCTs have found that varenicline significantly increases the probability of smoking cessation over bupropion, NRT, and placebo in smokers motivated to quit. Tonstad et al, 2020 report that in a pooled analysis of two large studies of about 1000 smokers each, the 12-month abstinence rates among those given varenicline, bupropion, and a placebo were 44%, 29.7%, and 17%, respectively. One meta-analysis of clinical trials found an odds ratio of 2.33 for abstinence on varenicline vs. placebo, 1.52 for varenicline vs. bupropion, and 1.31 for varenicline vs. NRT (Jordan, 2018).

As with NRT, the main limitation of pharmaceuticals seems to be that very few smokers use them. Tibuakuu et al., 2019 (Fig 2) find that roughly 6% of US smokers use smoking cessation medication. I did not look closely into why this is the case, but concerns about side effects, lack of knowledge, and generally low rates of quit attempts could explain low takeup rates. In the US, most insurance (including Medicaid) cover NRT and pharmaceuticals, so in nearly all cases the out of pocket cost for cessation aid is lower than the cost of continued smoking. I did not look into the cost for LMICs, but as of 2021, the WHO includes both bupropion and varenicline on their list of essential medicines (WHO, 2021).

As a next step, we should look for research on prior interventions that increased the availability of cessation medications. Because take-up rates are so low, and there is robust evidence they increase the probability of smoking cessation in RCTs, increasing the use of medications like varenicline could be a cost-effective intervention.

As a side note, there have also been efforts to create a nicotine vaccine (e.g. NicVax), but I’m not sure where in development/approval they are (clinical trials seem to have had mixed results).

6.6 E-cigarettes/cigarette alternatives for harm reduction

Electronic cigarettes, or e-cigarettes/e-cigs, are devices that produce vapor, usually containing nicotine, that is inhaled (“vaped”) by the user. They were originally developed in 2003 as a smoking cessation tool.

E-cigarettes have become incredibly controversial in the world of tobacco control, and most NGOs and public health organizations do not support e-cigarettes as a tool for harm reduction. One reason philanthropy and public health are so opposed to e-cigarettes is because as smoking rates have declined, tobacco companies have moved into the e-cigarette space (see PMI and BAT websites focused on smoke-free products). Marketing towards teens and use by high school students are also large concerns (Truth Initiative).

In 2008 the WHO stated that e-cigarettes are not a legitimate smoking cessation tool, and 37 countries currently ban the sale of e-cigarettes (GGTC, 2021). Note that only one country – Bhutan – bans the sale of tobacco cigarettes.

However, the UK is relatively accepting of e-cigarettes, and the NHS promotes them for harm reduction. The actual policy option for harm reduction would probably be changing the relative price of e-cigarettes and combustible cigarettes to incentivize smokers to switch. From a very quick search, it appears that e-cigarettes are cheaper per unit of nicotine than cigarettes in the UK (but with high startup costs). So the UK might serve as an example of the outcome of making e-cigarettes relatively cheaper while promoting them as a cessation aid.

6.6.1 Are e-cigarettes safe?

Taking the risks into account, the Royal College of Physicians, 2016 concludes that vaping is about 5% as harmful to health and society as smoking tobacco, and that it is unlikely that they do unexpected harm over the longer run. Warner, 2018 concluded that the mortality risk of smokeless nicotine is “no more, and quite likely less, than 10% of cigarette smoking” and that the cancer risk is probably close to zero. A 2008 study of Ruyan® e-cigarettes by Health New Zealand concluded that “Ruyan® e-cigarette […] appears to be safe in absolute terms on all measurements we have applied.” (Health New Zealand, 2008, page 20). Wilson et. al., 2021 estimate that vaping is 33% as harmful to health as smoking — much higher than the other estimates, though this still implies that e-cigarettes are much safer. Swedish snus is also an interesting case-study in favor of non-combustible tobacco being much less dangerous than cigarettes.

However, the public’s perception of the risk is very different. Warner, 2018 references a study that found 35.7% of adults in 2015 believed the harm associated with e-cigarettes was about the same as smoking, which even the most ardent anti-vaping organizations would not claim. A 2021 UK survey found 32% of smokers incorrectly believe vaping is more or equally as harmful as smoking (ASH, 2021).

While I think it is fair to conclude e-cigarettes are certainly not as harmful as combustible cigarettes, there is a large amount of pushback from public health organizations on the “95% safer” claim given the lack of long-term safety data. “E-cigarette advocates often claim that the products are 95% less harmful than conventional cigarettes. However, this assertion is unsubstantiated by quantitative evidence… e-cigarettes may present their own unique health risks, including to the respiratory and cardiovascular systems. Even e-cigarette manufacturers concede that the medium to long term risks of e-cigarette use are unknown.” (True Initiative)

E-cigarette users may inhale potentially harmful contaminants. The main risks:

- E-cigarette flavors can cause irritation & bronchiolitis.

- Vape liquid contains a solvent (typically propylene glycol or glycerine) that, when heated, can create carcinogens including formaldehyde and acetaldehyde.

- When devices are heated, the metal and plastic components can become aerosolized.

In most cases, the levels of toxins inhaled from e-cigarette vapor are very low and unlikely to cause long-term harm (Royal College of Physicians, 2016 pg. 79). However, one of the most serious health dangers from e-cigarettes, EVALI (e-cigarette or vaping use-associated lung injury), appears to be linked to vitamin E acetate in THC-containing vape products (CDC). This underscores the importance of regulating e-cigarettes to limit health risks.

Also, while there is not great long-run data, there is some evidence that long-term nicotine use (including from e-cigarettes) may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease (Benowitz & Burbank, 2016).

Additionally, the addictiveness of e-cigarettes is concerning. The addictive potential of nicotine depends on both the quantity of nicotine and the speed of delivery. Nicotine from vapor reaches the brain in about 10 seconds, and the nicotine concentration of e-cigarettes has been increasing (Raven, 2019; Truth Initiative, 2019). Nicotine addiction is particularly risky for young people, and there are concerns about nicotine addiction harming brain development and making young people more susceptible to other addictive drugs. If all new users of e-cigarettes are former combustible cigarette smokers, e-cigarettes would almost certainly benefit public health. But there are large public health concerns if the introduction of e-cigarettes is leading more young people to become addicted to nicotine.

6.6.2 Do e-cigarettes increase cessation?

From my brief look into the literature, RCTs have found that e-cigarettes are 50-80% more effective than traditional therapies (usually NRT) for smokers who want to quit. However, in observational data, e-cigarette use is not associated with increased probability of quitting. These two facts can be reconciled; at least one observational study found no association (or negative association) between vaping and cessation among less-than-daily users, and that cessation probability only increases among daily e-cigarette users (Wang et al., 2021). In other words, e-cigarettes may increase cessation among those actively trying to quit, but the availability of e-cigs alone might not increase the number of people trying to quit.

In the UK, data shows that e-cigarettes have rapidly become the most common form of cessation aid, replacing use of over-the-counter NRT (Royal College of Physicians, 2016 figure 6.5 pg 99). As of 2021, 7.1% (3.6 million) of the population used e-cigarettes. Of these, 64.6% were ex-smokers and 30.5% were dual users (using both e-cigarettes and cigarettes) (ASH, 2021). I have not found any studies showing population-level effects of e-cigarette availability on smoking rates.

Even if e-cigarettes did not help smokers quit, they could still have large public health benefits if they reduce the average number of cigarettes smoked per day by dual users. ASH, 2021 has useful data on the average number of cigarettes smoked by dual users; roughly half of dual users only vape occasionally (and so probably don’t substantially reduce cigarettes smoked), while the other half smoke somewhere between 1-4 fewer cigarettes per day than the average smoker in the UK.[14] In a brief literature search, I could not find a clear answer for how much harm reduction comes from reducing the number of daily cigarettes.

One concern about smoking cessation through the adoption of e-cigarettes is that e-cigarette users remain addicted to nicotine, which could increase the chances of recidivism to combustible cigarette use when compared with other cessation methods.

6.6.3 Are e-cigs a gateway to tobacco?

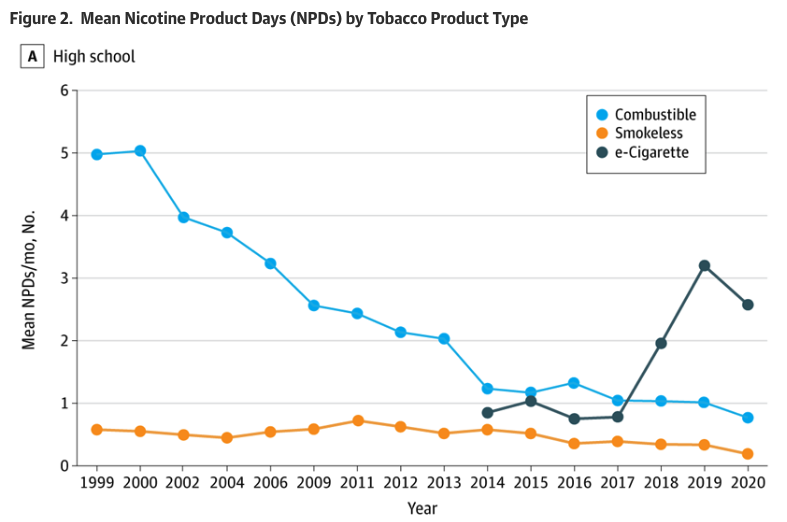

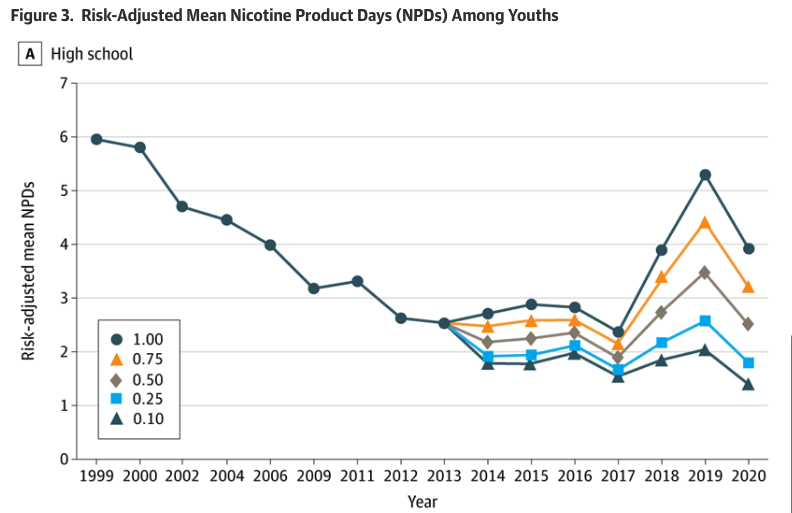

In the US and other high-income countries (HICs), e-cigarette critics are primarily concerned that teen vaping will increase nicotine addiction and be a gateway to cigarette smoking. After reading the literature, my take is that while vaping almost certainly did increase nicotine consumption among youth in the US, it likely did not increase smoking rates. Surveys of US grade 6-12 students show that nicotine (# of days used in the past 30 days) increased in 2017 as vaping (mainly Juul) became popular. The second graph shows the total risk-adjusted nicotine product days using different assumptions on the relative risk of cigarettes vs. e-cigarettes. Based on the literature, e-cigarettes are at most 10% as dangerous as combustible cigarettes (i.e. the bottom line in the graph), so risk-adjusted nicotine use has continued to decrease.

Longitudinal studies have found that e-cigarette use is associated with an increased risk of future cigarette initiation and current cigarette smoking, even after controlling for confounding variables (Soneji et al., 2017). However, Warner, 2018 points out various flaws in the controls used by these longitudinal studies, and suspects that teens who vape would have been more likely to smoke anyway. Based on the 2018 National Youth Tobacco Survey, the majority of vapers were also tobacco users. The survey also shows that of the 13.7% of youth who vaped in the past 30 days, about half vaped on five or fewer days (Glasser et al, 2020). From 2015 to 2018, youth daily smoking rates declined from 1.2% to .9%, and regular vaping (20+ days of the past 30 days) increased from 1.7% to 3.9%. Overall, it seems that while experimentation with vaping has certainly increased, most of the increase appears to be from infrequent use and, given declines in smoking rates, the overall health burden has likely decreased.

This literature is a bit convoluted because of differing definitions of who is a smoker, so before we take any strong stances about the harm-reduction potential of e-cigarettes, we should do a deeper dive into the literature on youth smoking and e-smoking rates. We should also look more into what policies could limit youth e-cigarette use.

6.6.4 Heated Tobacco Products

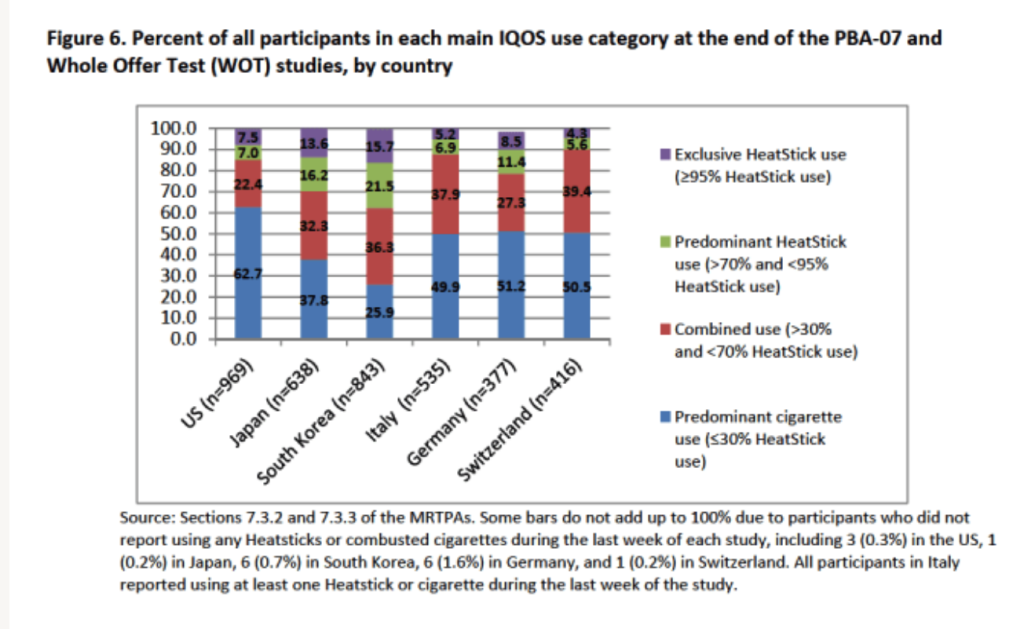

As the name suggests, heated tobacco products (HTPs) heat rather than burn tobacco. They are a relatively new product. The main player is Philip Morris International’s (PMI) brand IQOS, which launched in Japan and Italy in 2014. As of Feb. 2020, 14 million people used IQOS. Heated tobacco products are especially popular in Japan, where the brand Ploom is also popular.

I found the literature on safety of HTP vs. cigarettes even more convoluted than the e-cigarette literature. A large portion is funded by tobacco companies, and I did not find a single study that even attempted to estimate overall harm reduction. As with e-cigarettes, the WHO does not support HTPs for harm reduction, stating that while the toxicants in HTP smoke are “generally lower than those found in conventional cigarettes, the levels of some toxicants are higher and there are new substances absent in tobacco smoke which could potentially harm human health.” They also claim “there is no evidence to demonstrate that HTPs are less harmful than conventional tobacco products” (WHO, 2020).

From the few literature reviews I read, it seems that HTPs are less dangerous to health than traditional cigarettes, but more dangerous than e-cigarettes. HTP smoke has lower concentrations of potentially harmful chemicals than cigarette smoke (McNeill et al., 2018 – table 25). The FDA concluded that “the carbon monoxide exposure from IQOS aerosol is comparable to environmental exposure, and levels of acrolein and formaldehyde are 89% to 95% and 66% to 91% lower than from combustible cigarettes, respectively.” (FDA briefing on IQOS approval).

Since there is no data on long-term effects, the few existing safety studies rely on biomarkers. Ashley et al., 2021 reviews papers published from 2015-2021 and concludes that while there may be a correlation between HTPs and respiratory diseases, HTPs may have a lower risk of respiratory, cardiovascular disease, and cancer compared with traditional smoking. It might be worth getting someone with more expertise in biomedical research to review the studies in this literature review.

The data on whether HTPs increase cessation is also sparse. PMI makes some large claims, including that 72% of IQOS users in Japan completely switched from cigarettes to IQOS and 13.2 million adult smokers have switched to IQOS HTPs and stopped smoking (Tobacco Tactics, 2021; PMI). I did not find the data underlying these claims or any other credible research on whether HTPs reduce smoking prevalence. This is supported by Simonavicius et al., 2022’s review of the literature, which concluded: “No studies reported on cigarette smoking cessation, so the effectiveness of heated tobacco for this purpose remains uncertain. There was insufficient evidence for differences in risk of adverse or serious adverse events between people randomised to switch to heated tobacco, smoke cigarettes, or attempt tobacco abstinence in the short-term”. They do note that in Japan the rate of decline in cigarette sales did accelerate after the introduction of HTP (which supports the conclusion that HTPs can reduce smoking rates), though this could also be due to other factors.

6.6.5 Role of tobacco industry

One reason we should be skeptical about policies promoting e-cigarettes for harm reduction is the link between the tobacco industry and e-cigarettes. Statista reports that global revenues from e-cigarettes were over $20 billion in 2021, with most revenue from the US and UK. As the market for e-cigarettes has grown, tobacco companies have begun offering smoke-free products. Below are major tobacco companies and the smoke-free brands they own or are significant investors in (not a comprehensive list):

- Philip Morris International: IQOS (which has both an e-cigarette and HTP product) and Shiro nicotine pouches.

- Altria group (US branch of PMI): JUUL e-cigarettes and on! nicotine pouches.

- British American Tobacco: Vuse e-cigarettes, glo HTP, and Velo nicotine pouches.

- Japan Tobacco International: Logic e-cigarettes and Ploom HTP

- Imperial Brands: blu e-cigarettes, Pulze/iD HTPs, and ZONE X nicotine pouches.

In the US, 97% of e-cigarette sales come from brands owned by tobacco companies (Statistica, 2020). As the market for alternative nicotine products grows, it is likely that products will continue to be bought up by tobacco companies (for example, PMI is currently in the process of buying Swedish Match, maker of Zyn nicotine pouches). To the extent that current cigarette consumers switch to smokeless products, this could be seen as a positive move. However, the concern is that if these new products are marketed towards youth, they could stall progress on reducing tobacco consumption. If we move forward with tobacco control, we would need to consider this tradeoff.

6.6.6 BOTEC: E-cigarettes in the UK

I attempted a BOTEC (calculations here) of the annual value of e-cigarettes in the UK (compared to if they did not exist), since the NHS has accepted e-cigarettes for harm reduction and the UK has good data on e-cig users.

I found that the annual value of e-cigarettes in the UK (from lowered DALYs due to reduced cigarette consumption among e-cig users) is ~$16.6 billion. Of this, ~$13.1 billion is from estimated increases in smoking cessation and ~$4.1 billion from harm reduction among “dual users” who continue to smoke but likely reduced their daily cigarette consumption. I also subtracted about $500 million from the benefits to account for e-cigarette use among people who’ve never smoked, under the assumptions that (a) people in this group would not have smoked in the counterfactual, and (b) vaping is 5-10% as harmful as cigarette smoking.

The big sources of uncertainty in the BOTEC are:

- Of vape users who are former smokers, how many would have quit anyway, without the assistance of e-cigarettes? The evidence is mixed on how effective e-cigarettes are at increasing cessation rates at the population level. The main BOTEC assumes that using e-cigarettes increases cessation by 25%. As a lower bound, I assume that e-cigarettes do not increase cessation; as an upper bound, I assume that e-cigarettes are 50% more effective (figure taken from the aforementioned RCT result for smokers trying to quit).

- How much “healthier” are dual users who vape daily? I did not find good estimates of this in my quick search of the literature, and my current guess could be improved a lot. Based on Ash, 2021 (Table 2), it seems that dual users who vape every day smoke about 3.5 fewer cigarettes than the UK average of 10 cigarettes/day. I then took the estimates from one paper on incidence of cancer in Australia that included survey questions on the number of cigarettes smoked per day (Weber et al., 2021). They found that those who smoked 1-5 cigarettes per day had a 7.7% cumulative risk of lung cancer at age 80, while those who smoked 6-15 per day had a 12% risk. I took this info and guessed that vapers who lowered cigarette consumption lose on average 25% fewer DALYs from smoking.

- Does e-cigarette availability increase smoking initiation? This BOTEC assumes that e-cigarettes in the UK did not increase smoking rates. This assumption is based on the papers discussed above (Are e-cigarettes a gateway to smoking?). However, if some portion of smokers in the UK would not have been smokers in the counterfactual world without e-cigarettes, we should add the cost of increased smoking initiation to our value estimate.

6.7 Cigarette Taxes

From the literature, and my conversations with experts, there seems to be a consensus that cigarette taxes are the most effective single tool to reduce smoking rates. Based on a recent review of global evidence on tobacco taxes (Chaloupka et al., 2019), the price elasticity for tobacco in LMICs is approximately -.5 (ranging from -.2 to -.8).[15] This elasticity is higher than in HICs, and in general lower income populations are more responsive to price increases, so we might expect even larger demand responses in particularly poor areas. About half of the short-run response to increased prices is from reduced smoking prevalence, and the other half from continued smokers smoking fewer cigarettes. Because taxes also reduce smoking initiation rates, one expert I talked with suggested that the long-run response is about 2x the short-run response.

Unlike in many HICs, in LMICs cigarettes tend to be a normal good, so consumption increases as incomes increase. One key part of the WHO-recommended excise tax structure is increasing taxes so that cigarette prices rise faster than incomes. However, from 2008 to 2018, affordability declined in only ~35% of MICs and 26% of low income countries, compared to ~70% of HICs (WHO, 2021). On average, taxes make up 68% of the total price of a pack of cigarettes in high-income countries, 58% in middle-income countries, and 38% in low-income countries. As a result, prices for cigarettes are significantly higher in HICs (PPP $7.80, $4.99, $3.09 for HIC, MIC and LIC, respectively). (WHO, 2021). Excise taxes are lowest in Africa and the Middle East.

Challenges to taxes from the tobacco industry can be very strong, particularly in LMICs without sufficient resources to counteract their lobbying efforts. The tobacco industry is also very strategic at avoiding taxes by forestalling/front-loading sales right before tax increase, raising prices in anticipation of tax (so it looks like the tax was ineffective), offering discounts to price-sensitive customers, moving into low-price options, and lobbying for their preferred form of taxation (WHO 2021 tax manual page 43). An expert with experience researching the tobacco industry also told me that tobacco companies are often directly involved in smuggling, and in some cases fund the exact organizations tasked with preventing smuggling.

In addition to the share of excise tax, there is some nuance around the optimal form of taxation for tobacco outlined in the 2021 WHO technical manual on tobacco tax policy and administration. I included some notes in the appendix, but the main takeaway is that not all tobacco taxes are created equal, and there could be efficiency gains from not just increasing the level of tobacco taxes but also from restructuring existing taxes.

6.7.1 BOTEC: Cigarette Tax

I put together a very rough BOTEC of the value of a cigarette tax campaign, using the following assumptions:

- Cigarette demand has an elasticity of -0.5

- The campaign costs $1 million per year for three years.

- The campaign has a 10% chance of success, and speeds up a 10% retail price increase through tobacco tax increases by three years.

I found that such a campaign in Indonesia would save ~996,000 DALYs, with an SROI of ~3,319x. However, in a smaller country like Suriname, a campaign with the same cost would have a much lower expected return of ~6x.

A rough BOTEC suggests that if all costs remain the same, increasing taxes only clears our 1,000x bar in LMICs with populations > 100 million (i.e. Indonesia, Pakistan, Brazil, Nigeria, Bangladesh, and Russia – all of which already have large tobacco-control efforts). If we think the chance of success is more like 50%, then countries with populations >21 million meet the 1,000x bar. Even with a 100% probability of success, a tobacco tax that increased retail prices by 10% would clear the 1,000x bar in Suriname only if it cost less than ~$180,000.

While these numbers are all very uncertain (and rely on several questionable assumptions), the main takeaway is that cigarette tax advocacy can be very valuable but probably only clears the 1,000x bar if it affects a large smoking population or can be implemented cheaply with a high probability of success.

The major uncertainties in the BOTEC come down to:

- The cost of cigarette tax advocacy. One organization we talked with estimated that it cost them about $1 million per year to run a campaign in a new country, and that implementing a policy change will take at least three years. Tobacco control campaigns are relatively expensive because of industry pushback. The costs likely depend on legislative structure, amount of tobacco industry funding (which likely depends on the number of smokers), and GDP per capita. I don’t know enough about how costs scale with the size of the country to make a good guess of the cost in smaller countries, though presumably it scales somewhat with country size.

- How likely campaigns are to succeed. I set this to 10%, but I don’t have a great justification for this. We should do more research on past attempts to influence tax policy and estimate what proportion were successful.

6.8 Graphic Warning Labels

Graphic warning labels on cigarettes increase knowledge about their dangers, reduce positive associations with smoking, and increase motivation to quit (WHO, 2019 pg 8 ). The evidence that they actually reduce consumption is more mixed. Strong et al., 2021 randomized cigarette packages (some with graphic warnings, some blank) to smokers in the US and found no difference in cigarette consumption. The WHO points to New Zealand and Brazil, which both saw increases in calls to the tobacco quitline following warning labels on tobacco products (the warning labels included the tobacco quitline number) (Cavalcante, 2003; Li, 2009).

In the US, the FDA’s graphic warning label regulations have been challenged by the tobacco industry because of a lack of evidence of effectiveness. Based on comparing smoking trends in the US and Canada after Canada adopted graphic warning labels in 2000, the FDA estimated that the reduction in smoking rates attributable to the warning labels was .088 percentage points (or 0.4% of the US smoking rate). Huang et al., 2013 revisit the FDA’s findings and point out a series of flaws in the original analysis, namely that it was sensitive to control variables and the time period used. Their difference-in-differences approach finds that graphic warnings on cigarettes in Canada lowered smoking rates by 2.87 to 4.68 percentage points. I only briefly skimmed this paper — it would be worth doing a deeper dive into this study and others.

I would also be curious if there is any population-level data on whether warning labels can decrease smoking initiation. My brief literature search brought up several articles showing that warning labels increase negative perceptions of smoking — but none showing lower rates of initiation (e.g. O’Hegarty et al., 2006; Kees et al., 2006).

6.9 Marketing bans

Blecher (2008) Table 1 and Saffer & Chaloupka (2000) Table 1 both list reviewed studies on the relationship between tobacco consumption and advertising expenditure, and discuss some of the concerns with the literature on this topic. It seems like cross-sectional studies discussed (mainly using geographic variation in advertising) tend to find significant positive effects of advertising on cigarette consumption.

Advertising bans have been shown in various contexts to negatively impact per capita consumption:

- Saffer & Chaloupka conclude that comprehensive bans do reduce tobacco consumption. However, it seems limited advertising bans (e.g. only on TV advertising) have no effect, probably because advertising shifts to other sources.

- Nelson (2003) is another cross-country comparison of advertising bans in 42 developing countries and finds no effect. However, this paper apparently doesn’t control for cigarette prices, which seems like a major flaw.

- Bardach et al., 2021 report the following effect sizes based on their review of the literature: An “intermediate” media ban (including national TV, radio, or print media and some direct and/or indirect forms of advertising) lowers per capita consumption of cigarettes by about 1% (range 0%-13.6%) (see section 2.6). A “maximum level” ban (all forms of advertising, both direct and indirect, and ban on product displays) is associated with a 9% decline in consumption (range 5% – 23.5%).

Overall, the evidence suggests that advertising bans work when they are very strict and apply to all forms of media. However, the effect sizes are not consistent and there isn’t a clear consensus on whether more limited advertising bans have any effect.[16]

6.10 Other strategies

Some of the other most commonly used/mentioned tobacco control strategies I didn’t look into.

Legal aid/training. That is, training government officials to write better legislation/ fight back against the tobacco industry. Depending on how much you think better legal aid would increase the chances of a policy successfully passing, this could have large effects on the estimated SROI of tobacco control policies. Two organizations that work on this are the Anti-Tobacco Trade Litigation Fund and McCabe Centre for Law & Cancer.

PSAs. RCTs have found that anti-smoking PSAs change beliefs about smoking and can increase negative views towards smoking (e.g. Won Cho et al., 2017, a study of Korean college students). The CDC reports that its 2014 Tips PSA campaign helped at least 100,000 Americans quit smoking for good. On the other hand, I also found one RCT (N = 56) which found that anti-smoking PSAs actually increased participants’ probability of smoking during a break immediately following viewing (Harris et al., 2014). I haven’t read enough of this literature to get a good sense of what the expected effects from national PSAs might be.

Smoke-free policies (e.g. banning smoking in bars/restaurants).

Plain packaging laws. As of 2020, 17 countries had plain packaging laws for tobacco products (in 2019, Thailand became the first LMIC to introduce such a law). Cohen, et al., 2020 describes some of the legal challenges from the tobacco industry. I didn’t look into the literature on the effects of plain packaging laws, since I assumed they would be even lower than the effects of graphic warning labels — but I could be wrong here.

Lower nicotine content in cigarettes. The Biden Administration has proposed imposing a maximum nicotine level in all tobacco products in the US. Wilson et. al., 2022 modeled the effects of a hypothetical denicotinization policy in New Zealand, concluding that it may reduce smoking rates and increase vaping rates. This is an interesting policy, but it doesn’t seem to be a strategy being considered in LMICs, so I didn’t look into it closely.

Appendix and interesting side notes

Optimal Tobacco Tax Policy

The goal of tobacco taxes is to increase the price of tobacco as much as possible to reduce consumption as much as possible. So by “best” or “optimal” tobacco taxation structure, I mean the structure that leads to the highest prices (ignoring differences in government revenue).

Ad valorem taxes are taxes set to a percentage of a good’s value, which could be either the retail price or the producer price (e.g. a 5% sales tax). Specific taxes are taxes with a set amount per quantity (e.g. a $1 tax per cigarette). You can either apply these taxes on their own or in combination. You can also either apply taxes uniformly (i.e. the same on all tobacco products) or at a tiered rate (e.g. taxing differently based on cigarette length).

Some general takeaways from the 2021 WHO technical manual on tobacco tax policy and administration.

- Uniform taxes are better than tiered taxes. When you have a tiered tax structure that taxes differently on characteristics like cigarette length, this can cause consumers to switch to cheaper tobacco products rather than reducing smoking.

- In general, specific taxes (or mixed systems) lead to higher tobacco prices than ad valorem taxes.

- If using ad valorem (or mixed), you should have a minimum specific excise tax.

- When using specific taxes, you need to (preferably automatically) adjust the tax for inflation and for income growth. I’m not sure how many countries have successfully passed tobacco taxes that automatically adjust for inflation, but this is a particularly important goal for tobacco taxes since you can expect a well-funded pushback from the tobacco industry any time you try to pass legislation to adjust tobacco taxes for inflation.

Swedish Snus

Swedish snus is an oral smokeless tobacco product typically made of tobacco, water, sodium chloride, sodium carbonate, flavoring, and humectants (e.g. propylene glycol and glycerol to retain moisture) (Rutqvist et al., 2011). It is similar to American chewing tobacco, except it is typically sold in pouches and tends to be spit-less.

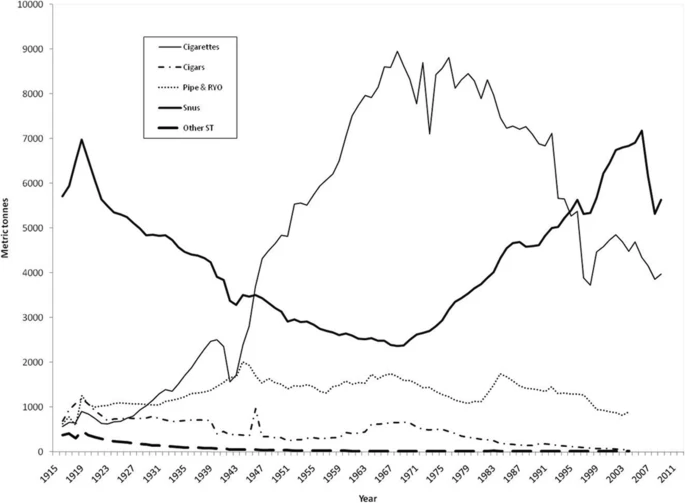

The EU has banned snus since 1992, but Sweden was given an exemption when it joined the EU in 1995. Sweden currently has the lowest prevalence of daily cigarette use in the EU (5%), but 20% of the population uses snus daily.[17] The epidemiological literature finds that Sweden has comparatively low levels of tobacco-related diseases compared with the rest of the EU (despite having high levels of tobacco use). Clarke et al., 2019’s review of the literature finds that snus has significant harm reduction benefits, particularly in reducing the incidence of lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. The trends in consumption of cigarettes and snus suggest that the two products are substitutes (as snus became more popular, cigarette consumption decreased).

As with e-cigarettes, Scandinavian health officials have warned that snus is not a safe alternative to smoking, and do not recommend snus for smoking cessation. However Lund & Lund, 2018 conclude that snus has contributed to decreasing cigarette consumption in Norway because:

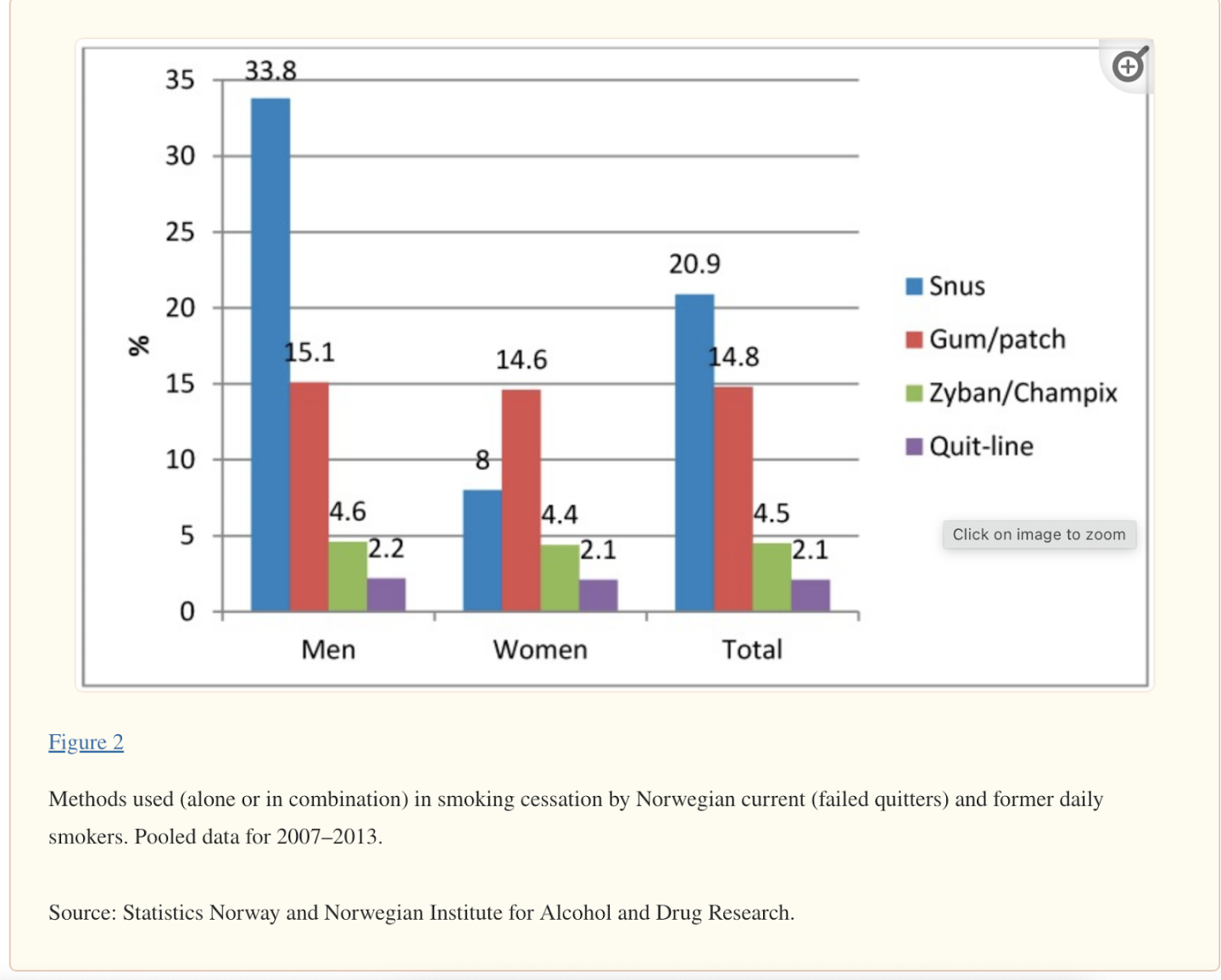

- Snus increases cessation. It is a popular cessation aid among smokers (figure below), many studies have shown that daily snus use is associated with high rates of quitting smoking, and the majority of snus users are former smokers.

- Snus seems to be an alternative to cigarettes for “tobacco-prone” youth, who would otherwise begin smoking. Youth snus users have characteristics that usually predict cigarette smoking. There has also been a rapid decline in smoking among youth in Norway since the 1990s.

- Snus may contribute to decreased cigarette consumption in continued smokers. In Norway, dual users have weekly cigarette consumption 40% below that of exclusive smokers (though the proportion of dual users is small).

Another interesting parallel to e-cigarettes is that the tobacco industry is a large player in the smokeless tobacco market. Philip Morris recently bought the main snus company (Swedish Match) for $16 billion (Hipwell & Gretler, 2022), and both Altria (PMI’s offshoot) and BAT have large shares of the US chewing tobacco market (Swedish Match). Additionally, a relatively recent product in the smokeless market is tobacco-free nicotine pouches (the main brand is ZYN, owned by Swedish Match).

Nicotine pouches seem to be safer than snus, and are a rapidly growing product in the US. There have been very similar concerns raised with nicotine pouches (danger of flavors, concerns about marketing to youth). However, as with e-cigarettes, most users of ZYN are current/former tobacco users (Patwardhan et al., 2021). Presumably, nicotine pouches would be even safer than e-cigarettes (given that the danger from e-cigarettes is inhalation of chemicals), but there still seems to be controversy due to lack of long-term data on safety.

Cessation and e-cigarettes

Hajek et al., 2019: RCT of 886 smokers in the UK using stop-smoking services. Randomized to NRT of their choice or e-cig starter pack (all given behavioral support for 4 weeks). The 1-year abstinence rate for the e-cig group was 18%, vs. 9.9% for NRT group — that is, e-cigs were 81% more effective than NRT.

Cox et al., 2019: non-randomized prospective study of 115 UK smokers. Participants chose either e-cigs, NRT, or a combination of both at a pharmacy. 62.2% of e-cig users reported complete abstinence at 4-6 weeks, vs. 34.8% of NRT alone — that is, e-cigs were 78% more effective than NRT. This study was not randomized, groups not balanced. But it did not include behavioral support.

Chen et al., 2022: US 2017 PATH cohort study of former smokers (N=1323) and smokers with recent quit attempts (N=3578). Self-reported use of e-cigarettes & other quit methods. Outcome = 12+ months of cigarette abstinence and tobacco abstinence in 2017. Use propensity score matching on covariates. 12.6% of quit attempters used e-cigarettes. Cigarette abstinence for e-cig users was 9.9%, vs. 18.6% for people who used no products — that is, the use of e-cigarettes for cessation in 2017 did not improve successful quitting.

Wang et al., 2021: Meta-analysis (64 papers from the US & other HICs). In observational studies (N=55) of adults who express some desire to quit, e-cig use is not associated with cessation. However, in observational studies that measure frequency, daily e-cigarette use was associated with quitting, but less-than-daily use was negatively associated with quitting. In other words, smokers who occasionally vape are less likely to quit, but smokers who vape daily are more likely to quit. In RCTs (N=9), smokers who were provided with e-cigs were more likely to quit (relative risk = 1.555). The cessation rate for conventional therapy was .086, and e-cig use increased absolute cessation rate by .04.